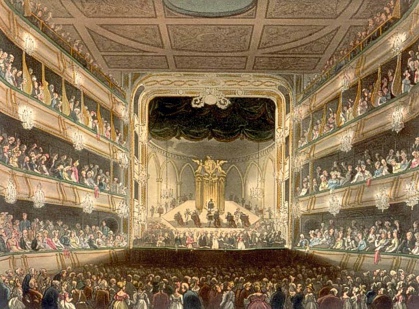

Willis's Rooms, London

Willis's Rooms, LondonPiatti's second visit to England was in 1846 and we find that he was at once engaged as a soloist in eight or nine concerts in London during the season, including Mrs. Anderson's Annual Concert.

The concert of the greatest importance to Piatti at which he played during this season was the Benefit Concert of the Director of the Musical Union at Willis's Rooms, as it was the first occasion on which he took part in public in a string quartet. At that time although the concerts of the Musical Union had ceased to be private meetings at the director's house, and were given in a public hall, yet they were so far private that only subscribers were admitted to the concerts.

An exception was however made in the case of the Director's Benefit Concert which was advertized in the papers and for which tickets were sold, and which was therefore a public concert in every sense of the word. Piatti played in a quartet by Mozart and in one movement of a quartet by Spohr.

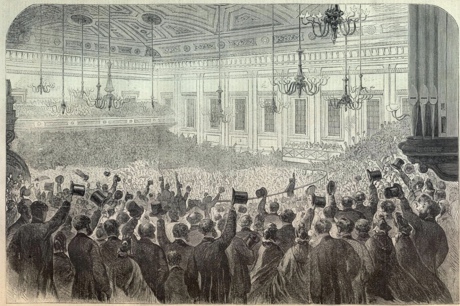

Covent Garden Theatre

Covent Garden TheatreHe was again engaged to play in the orchestra at the Opera. He also played in Jullien's Concerts d'Eté which were given in Covent Garden Theatre; and it is wonderful to think what Jullien's band must have been, when we know that at the same time there were playing among the first violins, Sainton, Ernst, Sivori and Vieuxtemps.

Verdi came to England in 1847 for the production at Her Majesty's Theatre of his Opera "I Masnadieri," which was written expressly for the English stage. The work did not prove a success, but it contained an incidental obbligato for the violoncello, the performance of which by Piatti was much applauded.

This is not the place to go into the operatic squabble which caused much excitement to the public and considerable discomfort and inconvenience to artists half a century ago. Suffice it to say that in the end all the existing orchestral arrangements fell through owing to the post of conductor at Covent Garden being taken by Sir Michael Costa with the understanding that the orchestra of Her Majesty's Theatre was to go to Covent Garden. However Lumley, having the management of Her Majesty's Theatre, engaged Balfe to form an orchestra for the Opera there, and Balfe, whose acquaintance with Piatti dated from the days when the orchestra at Bergamo was "trotto basso," secured him to lead the violoncellos, a post which he held for several seasons.

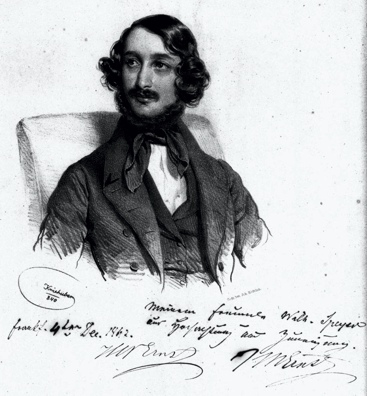

François Servais

François ServaisPiatti played also on one occasion at a concert and used his Amati violoncello which had been in the maker's hands and been altered, and had only come back into his possession on the morning of the Concert.*[When recently Herr Kubelik played on a violin which had not been in his hands before the day of the Concert someone said “Such is the rash confidence of youth."] He played one of his own works "Une Prière" which, as he had frequently played it with success, he regarded as his Cheval de bataille. Servais, the violoncellist, had composed a "Souvenir de Spa" which he used constantly to play, and he once said to Piatti, "'Une prière'” is your 'Souvenir de Spa.'" However at the concert in London the performance was a failure according to Piatti's own opinion.

It will be remembered that the work selected by Piatti for his first appearance at a Philharmonic Concert was a Fantasia by Kummer. Hellmesberger, who was a wit as well as a violinist, said of Servais and Kummer "Wenn ich Kummer spielen höre, thut es mir sehr weh (Servais); und wenn ich Servais spielen höre, macht es mir Kummer."

Besides playing at the Opera Piatti frequently played solos at the National Concerts which were given at Her Majesty's Theatre in the autumn of 1850 under the direction of Balfe.

Exeter Hall

Exeter HallHe also played for some years with the Sacred Harmonic Society under Costa. Haydn's "Seasons" was produced by that Society in Exeter Hall on December 5th, 1851. It was the opening concert of the season and the following passage occurs in the review of the performance in the "Musical World":—"The only important change remarked in the orchestra was the substitution of Signor Piatti for Mr. Lindley, as principal violoncello. The father of the orchestra may console himself, on retiring from public life, with the assurance that the place he has occupied with so much distinction for more than half a century will be worthily filled by his young and gifted successor now, beyond comparison, the first violoncellist in Europe."

The monster Concerts which were given in those days were fatiguing. A critic in the "Morning Post" writes "The tinkling of a pianoforte for four hours on a stretch becomes very wearisome."

With reference to such concerts a story was told by Piatti of an incident at one of Glover's monster concerts which used to be given at Drury Lane Theatre. These concerts began at two and continued till seven or even later. On one occasion it was arranged that Paque, on the violoncello, and Gilardoni, on the double bass, should play one of Corelli's Sonatas about the middle of the programme; when, however, the time for them to perform came, a lady said, "I must sing now if I am to sing at all, as I have to sing at the Opera tonight." Then another singer came forward with a similar excuse; until by degrees the Corelli performance was pushed off and off to the end of the concert, when the audience were possibly beginning to sigh for something a little less classical. When Paque began a well known gigue by Corelli, someone in the gallery immediately struck up the then popular air, "A perfect cure" the first three notes and the rhythm of which are identical with the opening of the gigue, and this was presently taken up by the audience in the gallery generally. Gilardoni went off at once in a rage, but Paque continued playing, unconscious in the hubbub that Gilardoni had gone, till looking round and missing his companion, he also picked up his instrument and fled.

From 1846 onwards Piatti was constantly in London, and England gradually became a country as dear to him as Italy. Indeed he probably had more friends in England than in his native land. His setting of Tennyson's "Swallow, swallow" was the expression of his keen love for England, and under the blue skies of Italy, he often sighed for the haze and cloud and neutral tints of the north.

In the spring of 1847 Mendelssohn visited London for the last time, and a private matinée in his honour was given by the Beethoven Quartett Society on the 4th of May. The programme, entirely selected from the works of Mendelssohn, except that he himself played Beethoven's 32 variations, consisted of the Quartett in D opus 44, the Octett, in which Piatti played, the Trio in C Minor and Lieder ohne Wörte. One who was present writes, after an interval of more than half a century, "It was a most memorable performance and made an impression never to be forgotten; Piatti played magnificently, Mendelssohn's playing created great enthusiasm; Vieuxtemps was grand." Another musical event in London happened to occur on the evening of the same day, the début at Her Majesty's Theatre of Jenny Lind.

When the Beethoven Quartett Society gave a similar matinée in honour of Spohr, Piatti took the first violoncello part in the double quartett in E minor, which was of course led by the composer.

Sterndale Bennett, an enthusiastic admirer of Piatti, composed and dedicated to him a Sonata Duo in A minor for Pianoforte and Violoncello which was performed by them at a concert, although it had been only completed the same afternoon. The same work was performed by them again at the first Concert of the Quartett Association at Willis' Rooms on April 28th, 1852.

Bernhard Molique

Bernhard MoliqueAnother work composed for and dedicated to Piatti was Molique's Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra which was first performed at a Philharmonic Concert on May 2nd, 1853. There is no more effective Concerto for the Violoncello with Orchestra, and it has been frequently played by Piatti in Germany. When the work was completed, Molique asked Piatti to come and try it, and a gentleman who was present says that though in manuscript and abounding in technical difficulties which would have staggered any other performer, it presented no difficulty to Piatti, so that Molique afterwards said to a pupil, "Dat Piatti is de debil, he play my concerto at sight." The critic of the "Musical World" writes of this performance at the Philharmonic Concert:—

"In Signor Piatti Herr Molique found an executant capable of giving the best effect to his concerto. Seldom has this unrivalled player appeared to greater advantage. His execution of the passages and tours de forte was perfect, while his tone and expression in the cantabile phrases might have afforded a useful lesson to any vocalist."

Crystal Palace

Crystal PalaceSir Arthur Sullivan also wrote a violoncello concerto for Piatti which was produced at the Crystal Palace in 1866.

Piatti studied composition chiefly in England under Molique. They were great friends and had the highest admiration for each other. Molique had studied the violin at Munich under Rovelli a cousin of Piatti's father. Rovelli was principal violin in the Court Orchestra at the time, but he was also fond of Bohemian society, so that Molique had sometimes to wait half the night for Rovelli to come home and give him a lesson.

Molique was very strict in his harmony and counterpoint. On one occasion Piatti defended a progression which he had written, saying, "But Meyerbeer has used it." "Meyerbeer" said Molique, "Meyerbeer must not be taken as an authority." On another occasion Piatti played a composition of his own in the presence of Regondi, who exclaimed, "Bravo, bravo!" "I like it not," said Molique.

Piatti was of opinion that Molique would have had many pupils in England, had he been better acquainted with English. Molique was once in a cab with a lady, who, being uncertain of the way, asked him to make enquiries from the cabman. Molique put his head out of the window and said, "Who are we?" The cabman answered, "If you don't know, I'm sure I don't." On the other hand Molique told a story of his having been summoned on a jury and when the clerk of the Court called out, "Mr. Mollike;" "I answer not," said Molique.

Piatti as a bachelor was in the habit of dining at a restaurant in Golden Square, where he used to meet Mazzini, Orsini and other Italian refugees. Strangely enough on the floor above Orsini, Prince Napoleon, afterwards Napoleon III, used to dine.

In 1856 Piatti was married at Woolchester near Stroud to Mary Ann Lucy Welsh, the only daughter of Mr. Thomas Welsh, a well known professor of singing. There were four children of this marriage, but one daughter only grew up. The marriage was not a happy one, and ended in a mutual arrangement to live separately. Madame Piatti died in Italy a few weeks after her husband.

On more than one occasion between 1861 and 1864 Piatti acted as one of the judges for the prizes given by the Society of British Musicians for string quintetts and took part in the performances of the successful works.

The action of the Philharmonic Society in inviting Signor Piatti to perform a work of his own composition at one of the Jubilee Concerts of the Society on Monday, July 4th, 1862, given under the direction of Sterndale Bennett, was a complitnent of which any artist might well be proud. The whole of the seats for the Concert were taken before the end of the previous week. The work selected by Piatti was his "Thème varié" which is described by a critic as brilliant and well written and as having been received with the most flattering applause.

As Piatti, chiefly owing to his work in England, became more independent he felt that a small furnished house would give him greater comfort than lodgings, and one day walking up Park Lane, he observed that the pseudo-gothic house, well known to all Londoners, which was for many years in the occupatior of Sir Travers Twiss, was to be let. The situation seemed an agreeable one, and the house not too large. Piatti accordingly enquired what the rent was. It need hardly be added that he did not take the house.

Piatti at this time occupied rooms over a chemist's shop at the corner of Queen's Gardens. His father came to see him in England and arrived by sea at the London Docks. As he could not speak a word of English, his son had provided him with the address written on paper.

The paper however had been lost, so the father directed a cabman to drive him to "Cooen Garden" as an Italian, who did not know English, might attempt to pronounce Queen's Gardens. The cabman took him to Covent Garden.

Thence a police constable, not understanding what he wanted, conducted him to Bow Street, and sent across to the Opera House for an interpreter. Signor Monterasi, the prompter, who, as has been said, was a native of Bergamo, and who was probably the only person in London besides his own son to whom Antonio Piatti was known, came and, was able immediately to send Piatti to his son's address. The father seemed to think it as natural that he should meet Signor Monterasi in London as in a small town like Bergamo.

While staying with his son, Antonio Piatti was in the habit of going out alone. His son wished him to take the precaution of having a card with the address on it, but this the elder Piatti refused saying that he knew how to ask to be directed to the house. One day he lost his way. He went up to a gentleman in the street and said "Chemist." The gentleman called a cab and said to the driver," This gentleman must be ill, drive him to a chemist." The cabman drove to the door of the very chemist over whose shop Piatti lodged.

Once, on getting into an omnibus in London, Piatti by accident put the point of his umbrella close to the face of a passenger already seated in the omnibus. The latter was much annoyed, and paid no heed to the apologies of Piatti who, he said, had nearly put his eyes out. At last a third gentleman said to Piatti "Never mind, Sir, your hands are of much more value than his eyes."

Reference has been made to Piatti's acquaintance with Mazzini. On one occasion when travelling to the south Piatti, on reaching the Italian frontier, remembered that he had a volume of Mazzini's works in his possession. The discovery of such a book on an Italian at the time, which was before the accomplishment of the unification of Italy, would have led to his imprisonment, and he felt that the only thing to be done was to put a bold face on the matter. He therefore opened the book and read it deliberately in the Custom House. The officers searched his luggage, but it did not occur to them to enquire into the nature of the work which was open under their eyes. Their action was not dissimilar from that of a London police constable who, during the dynamite scare in London, inspected a gentleman's bag at the Law Courts and passed it; the gentleman afterwards complained to a friend of the action of the constable and was told that the police had instructions to examine all packages to see that no dynamite was brought into a public building. "That is too amusing," was the reply, "My bag is full of dynamite, which I am taking into the country to blow up the roots of trees."

Piatti himself was indirectly connected with dynamite outrages in London. He found in a book shop an old and rare Italian volume which he purchased, and it struck him that the attendant in the shop did not know much about his second-hand books or take much interest in them. On the following day Piatti received a visit from a detective officer from Scotland Yard. The attempt to blow up London Bridge had just taken place, and the second-hand book shop which Piatti had visited had been discovered to be but a screen for a dynamite store. The police authorities having found Piatti's address in the shop were anxious to ascertain if he could identify anyone whom he had seen there on the previous evening. It is to the credit of the Metropolitan police that the book shop had been so well watched and a visitor to it so quickly traced.

Piatti, who was a keen collector of old books, on another occasion went into a shop in Great Portland Street, and bought a quantity of old music. Turning over the pages, the shopman came on one piece which bore Hullah's signature, and said that he could not part with that as he collected autographs. Piatti assented and took the rest of the music. Among the works which he so purchased he found an opera by Handel and in it two bars of accompaniment added to relieve the voice, in Handel's hand-writing, a far more valuable autograph than that of Hullah.

On another occasion he bought a sonata for the violoncello by Boccherini for two or three shillings at White's, a second-hand music shop in Oxford Street. He added an accompanient to it and played it in public. He afterwards avent to White, who, as he had noticed, had another Boccherini sonata and asked the price of it. White demanded fifteen shillings. Piatti said, "But I bought one for two or three shillings". "Yes" replied White, "but you had not played it in public then!"

A silver violin was for a long time exposed for sale in a shop at the corner of Leicester Square, and this as a curiosity had frequently attracted Piatti's attention. It was ultimately bought by Mario, and found to have but a miserable tone; probably worse than the biscuit tin and piece of wood which may sometimes be seen in the hands of a street performer.

There was a viola by Stainer which Piatti had seen in Milan and at that time the owner was asking three thousand francs for it. A clever dealer in curiosities afterwards came to England with a collection of instruments to be sold and among others this viola, on which a reserve price of three hundred francs or £12 was put. The sale took place at Messrs. Puttick and Simpson's Auction Rooms, and when the viola was put up Piatti immediately bid 25 guineas for it and became the purchaser at that price. The dealer afterwards came to Piatti and told him that he was a ruined man, as he had made a mistake as to the reserve bid, which should have been not 300 but 3,000 francs. Piatti told him that the owner might cancel the sale and have the instrument back, but he heard no more of the matter. It was a not uncommon practice to change the head of an instrument when it was done up; and this viola, instead of a scroll, bore a carved head which was certainly not by Stainer. Opening one of the side boxes in the case, Piatti found in it the original head. He subsequently sold the instrument in Berlin for £180; a handsome profit no doubt. But the viola had of course only been bought as an investment and we cannot grudge to an artist the profit which such a transaction represents.

The knowledge of a good instrument like any other knowledge is only gained by long and persevering study and there is no reason why the man, who has, by his industry and ability, acquired this knowledge, should not benefit thereby.

The artifices of concert givers are exposed in a story about a man named Calcraft, who was giving a concert at Exeter Hall, and advertised "Sivori will arrive expressly for this concert." Piatti happening to meet Sivori on the day of the concert in London said, "You arrive late." Sivori did not understand what he meant, never having heard about the concert, so Sivori and Piatti went off to Exeter Hall together and heard Calcraft come forward and say, "Ladies and gentlemen, I am sorry to say that Signor Sivori has failed to keep his engagement." Piatti wanted Sivori to show himself on the platform, but he would not do so.

Sivori although he had been many years in England had but little knowledge of the English language. At a concert at which he played, and at which Henry Russell, the composer of "Cheer, boys, cheer," sang, the latter was encored. Sivori was jealous of the applause given to the popular singer. The next morning in the "Times" there was a long report of a speech by Lord John Russell, and Sivori's friends teased him by handing him the paper saying, "You see the 'Times' only speaks of Russell."

The following is a story of graceful tact on the part of Lady Benedit, now Mrs. Lawson. Lady Benedict asked Piatti to play at a party at her house and afterwards sent him a cheque for fifteen guineas. Piatti's fee at the time was twenty guineas, but of course he did not mention the fact. Later in the season Lady Benedict, having heard of her mistake, invited Piatti to dinner and asked him to bring his violoncello. It was quite a family party; but a day or two afterwards Piatti received a cheque for twenty-five guineas. This is in happy contrast with the cases, now we may hope rare, in which artists have been invited to dinner and then asked to perform. Liszt on such an occasion struck a few notes on the pianoforte and then said to his hostess, "Madame, j'ai payé mon dîner." Chopin under similar circumstances said, "Madame, j'ai si peu dîne." But perhaps the happiest of all was the vocalist who said "I can dine or I can sing, but I cannot do both."

Piatti experienced a peculiarity of the late Lord Dudley, who had such a prejudice against guineas that he preferred to pay twenty-five pounds to a fee of twenty guineas.

On one occasion Piatti was travelling to the north of England where he was to play at a private house. He had his instrument in the carriage with him, and got into conversation with a fellow traveller, an English nobleman, who asked him where he was going. Piatti told him the name of the station. "That is a small place," said the nobleman and then added, "but perhaps there is a fair there."

Brescia

BresciaEngland was not the only country where Piatti passed unrecognized. He was at Brescia with Lord and Lady Battersea and was showing them the principal objects in the town when a local guide came up to him and said, "You are not from this place. I know Brescia and can show them everything and we will divide the fee."

At Arnheim, Piatti had to play a concerto with the orchestra in which there was a passage where a violoncello of the orchestra had to play in thirds with the solo instrument. At rehearsal the passage was out of tune. Piatti looked round, and, seeing that the orchestral player was smoking suggested that he should put down his cigar and that they should try the passage again. But the second attempt was no better than the first so Piatti said, "Never mind, I will play it in thirds myself." After rehearsal he was walking away when he was overtaken by the orchestral 'cellist who asked him for his photograph. Piatti said, "I have not one here, but if you will give me your address I will send it from London." The violoncellist handed him a visiting card on which was engraved, "Baron von Amerongen, Grand Chambellan de sa Majesté le roi." Piatti said "I am afraid that you must have thought me very rude at rehearsal, but I did not know that I was speaking to an amateur." The Grand Chamberlain replied, "Oh ! I am much obliged to you; they all pay me compliments here, and I am grateful to you for telling me the truth."

At Newcastle Piatti went to the theatre to see a performance of "Don Pasquale." To his surprise Thalberg appeared on the stage in the character of the notary. The actor who should have played the part had been taken

Besides playing many times at the Philharmonic Concerts, Piatti played frequently at the Crystal Palace and at other orchestral concerts both in England and on the continent. Yet it is as a performer in chamber music that he will ever be best remembered.

Ernst

ErnstAfter the Musical Union had been converted by Mr. John Ella, from a private association to a public society for giving concerts of chamber music, Piatti for several seasons occupied the post of principal violoncellist, the quartets being led by Sivori, Ernst, Vieuxtemps, Sainton, Joachim and others. The meetings of the Musical Union were at first held in Willis' Rooms. When they were transferred to Saint James' Hall, the performers occupied seats in the middle of the room in the position recently adopted by the Joachim quartet.

It was for these concerts that Mr. Ella originated the publication of analytical programmes. These programmes were issued to subscribers before the concerts and thus gave them some useful information about the works which they were to hear. The Bach Choir made an attempt to recur to this practice but not with success. Life is now at too high a pressure, people attempt to read their books and to listen to music at the same time with the usual fate of those who try to do two things at once. In a proof of one of the Musical Union programmes, Piatti noticed a paragraph which began "This is perhaps one of the least interesting of Haydn's quartetts." Piatti said "You cannot print that, people will ask why the quartett is played." There was not time to make much alteration in the proof, but when the programme was issued Piatti read, "This is perhaps one of the most interesting of Haydn's quartetts."

Vieuxtemps

VieuxtempsThe Popular Concerts were established by Mr. Arthur Chappell in 1859; Piatti may almost be regarded as one of the promoters of that enterprise so keen was his interest in it, and until his final retirement he constantly held the post of violoncellist, the concerts at which he did not appear being few in number. Thus began his lifelong association with his dear friend Strauss and with Ries, whose connection with these concerts as second violin was as long as that of Piatti.

Through the Popular Concerts Piatti made many friends and acquaintances. Among the latter may be classed a violoncello player whose post is a responsible one though he has not risen to the top of his profession. The stage door from the hall occupied by the Christy Minstrels opens on to the stairs leading from the artists' room at St. James' Hall. Piatti was descending the stairs one evening when this stage door opened and a man with his face blackened greeted him, "Ah! you're Signor Piatti, the 'cello player of the Monday Pops. I'm the principal 'cello player of the Christys."

The most important of Piatti's compositions, or at least the works which gave him the greatest pleasure in composition, were his sonatas for violoncello and pianoforte written for the Popular Concerts. The first sonata was written at Cadenabbia and was produced at these concerts on Monday January 5th. 1885 when it was performed by the composer and Madame Haas; and Signor Piatti was recalled three times by a delighted audience. The work was repeated on Saturday February 28th.

At the last concert of the same season, on March 30th, 1855, Piatti produced his "Bergamasca." A critic explained that a Bergamasca was a dance resembling a Saltarello having its origin at Bergamo. Piatti himself however when asked for an explanation of the name said, "I don't know, I found the word in a dictionary." The rhythm which he has adopted is the rhythm of a country dance of the neighbourhood but the dance is not now known by the name of a Bergamasca.

The second sonata, in D, was written the following year while he was recovering from the injuries received in a serious accident which nearly cost him his life and which is mentioned later, and was produced at the opening of the concert on Monday April 4th, 1886 by the composer and Miss Agnes Zimmermann. The sonata consists of three movements, the last being an air with variations, all based on the same principal theme.

The third sonata was produced in 1889, the fourth in 1893, the fifth and sixth, which have never been published, in 1895.

Besides playing at these concerts, as everybody knows, the same quartet party habitually visited the principal towns in England. On one occasion as they went to their hotel at Nottingham, they saw a placard "Herbert Reeves will arrive" and below it in smaller type "Joachim, the friend of Emperors and Kings. Piatti the king of 'Cellists. Ries the First of Second violins." Again they saw "Herbert Reeves will arrive." And finally "Herbert Reeves has arrived." When they reached their hotel they despatched a messenger to the organiser of the concert begging him to assure them if it was really the case that Mr. Herbert Reeves had arrived.

At one town visited in this way Piatti told the hotel porter to be careful of the violoncello case which he was taking off the omnibus as it contained a very valuable instrument. The portet said "Is it a Joseph?" "Better than that," said Piatti. "You don't mean to say it is a Strad'," replied the porter. On another tour the pet Strad' was very nearly the subject of what lawyers call "larceny by trick." After a concert, a gentleman carrying a violoncello case came into the room where Piatti was putting away his instrument. He placed the case near Piatti's and, producing a violoncello, for which he said he had given a good price which he could ill afford, begged Signor Piatti to give him his opinion of the instrument. Piatti was unwilling to do this, but, yielding to entreaty, examined the violoncello and then informed the purchaser that he had been thoroughly cheated as it was a very poor instrument. After some further conversation the gentleman left. A minute later an attendant ran into the room, calling out, "Quick, Mr. Piatti; that gentleman is putting your violoncello on to his cab." Piatti ran down just in time. There was a profusion of apologies for the mistake of cases, and the Strad' was saved.

During the last twenty years of his residence in London, Piatti lived at No. 15, Northwick Terrace. The care taken by his landlady, Miss Freeman, of his property is exemplified in another Strad' adventure. One evening a man drove up to her door in haste, saying that a gentleman, whom Miss Freeman knew to be an intimate friend with whom Piatti frequently played, was in a great dilemma, as he had friends with him who wished to have music but he had no violoncello, and that he would be most grateful to Signor Piatti if he would lend his instrument for a few hours; the greatest care should be taken of it. Miss Freeman however did not fall into the trap.

Of Miss Freernan's solicitude for himself Piatti was ever mindful; and a legacy to her in his will was accompanied with the words, "In token of gratitude for the attention shown to me during my stay in her house."

Purchase the LPR recording of Piatti's works for solo cello here.